Three Ways to Lose Data (And How the Outbox Pattern Prevents It)

Well, about the outbox pattern I've read in one of the posts made by Oskar Dudycz, and second time it was in better software design episode, so as they say three times a charm, when I was practicing with go-event-driven from three dots lab with one of the modules about theory and implementing in practice I decided that I should give it a deeper dive. I will try to shed some light on when and why it could be useful to use it. The examples are picked from one of the projects made along with the mentioned training.

The need for this kind of solution, could happen when you need to maintain consistency between database writes and event publishing in high-traffic, distributed systems. Along the way I will explore a couple of reasons why this pattern is solving some of the possible problems with examples in go.

The Business Context

Our ticketing system had a problem. We relied on a third-party service to handle ticket bookings, but it couldn't handle the traffic spikes during popular shows. When a big concert went on sale, the third-party service would go down, and our customers couldn't buy tickets.

The solution seemed straightforward: handle bookings ourselves and notify the ticket provider asynchronously through events. We'd check seat availability, store the booking in our PostgreSQL database, and emit a BookingMade event that other services could consume.

Simple, right? Not quite.

The most critical constraint in our system is preventing overbooking. We can't sell the same seat twice. This means our seat availability check and booking insertion must be atomic - they must succeed or fail together. When you add asynchronous event publishing to this equation, things get tricky fast.

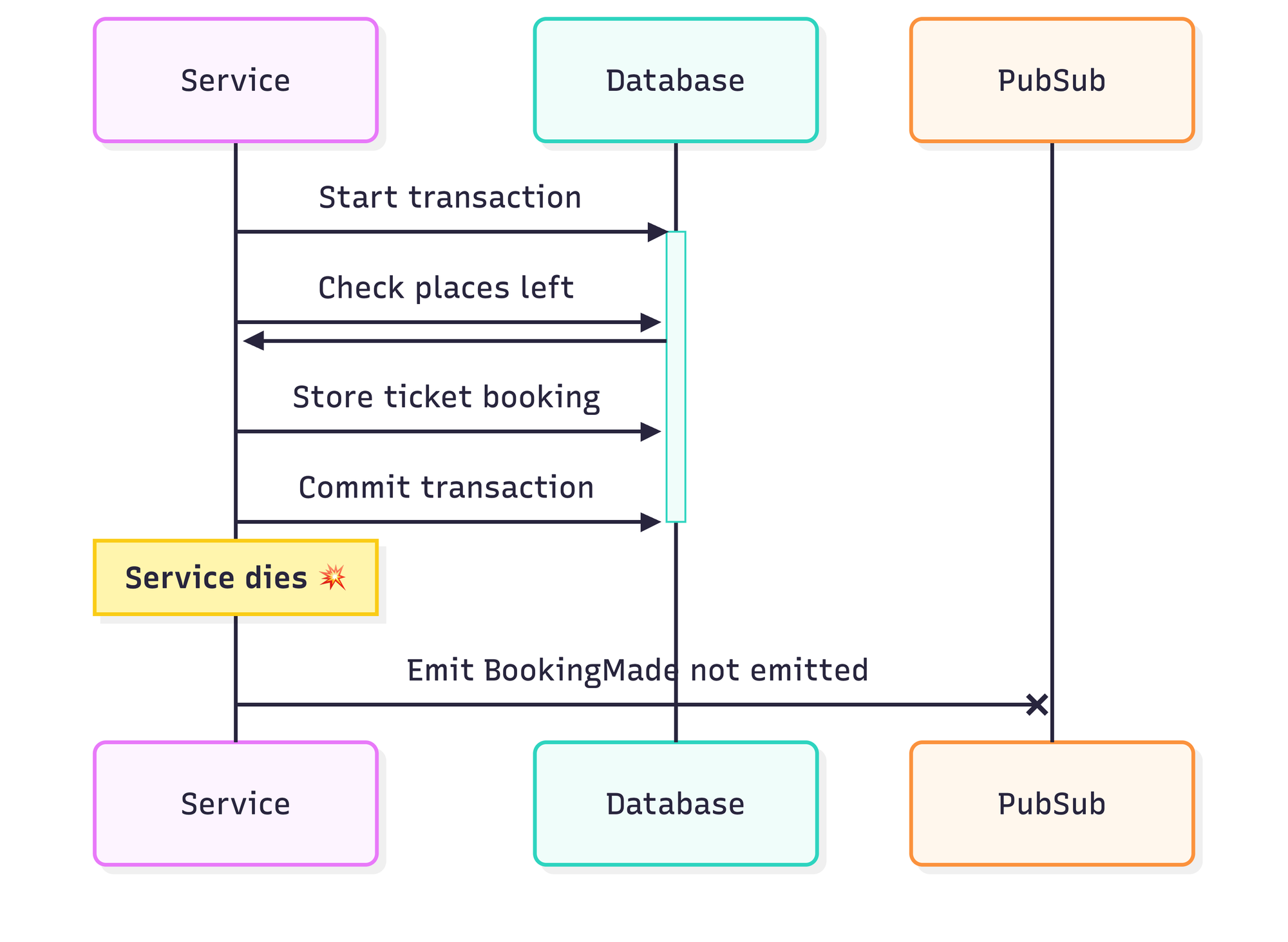

Scenario 1: Commit First, Publish After (The Lost Event)

Let's start with what seems like the most intuitive approach: complete the database transaction first, then publish the event.

Here's what the code might look like:

func (b BookingsRepository) AddBooking(ctx context.Context, booking models.Booking) error {

tx, err := b.db.BeginTxx(ctx, &sql.TxOptions{Isolation: sql.LevelSerializable})

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer tx.Rollback()

_, err = tx.ExecContext(ctx, `

INSERT INTO bookings (booking_id, show_id, number_of_tickets, customer_email)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4)

`, booking.BookingID, booking.ShowID, booking.NumberOfTickets, booking.CustomerEmail)

if err != nil {

return err

}

var remainingSeats int

err = tx.QueryRowContext(ctx, `

SELECT (s.number_of_tickets - COALESCE(SUM(b.number_of_tickets), 0))

FROM shows s

LEFT JOIN bookings b ON s.show_id = b.show_id

WHERE s.show_id = $1

`, booking.ShowID).Scan(&remainingSeats)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if remainingSeats < 0 {

return ErrNoPlacesLeft

}

if err := tx.Commit(); err != nil {

return err

}

// 💥 THE BOOM

event := BookingMade{

BookingID: booking.BookingID,

ShowID: booking.ShowID,

NumTickets: booking.NumberOfTickets,

}

return b.publisher.Publish(ctx, event)

}What Goes Wrong

Well, you can easily guess, we have the transaction committed to database, but the event is never published. For any reason the service is down, service crash, loses network connection or killed by the orchestration, we have a persistent booking added to database, but the event is lost forever and never distributed to any listener.

The outcome

- The booking exists in your database

- Your customer sees a successful purchase

- But third-party never receives the event

- No ticket is generated

- The customer shows up at the venue with no valid ticket

Why It's Dangerous

This is a silent failure. No error is thrown, no alert fires, and you might not discover the problem until customers start complaining. By then, the concert might be over.

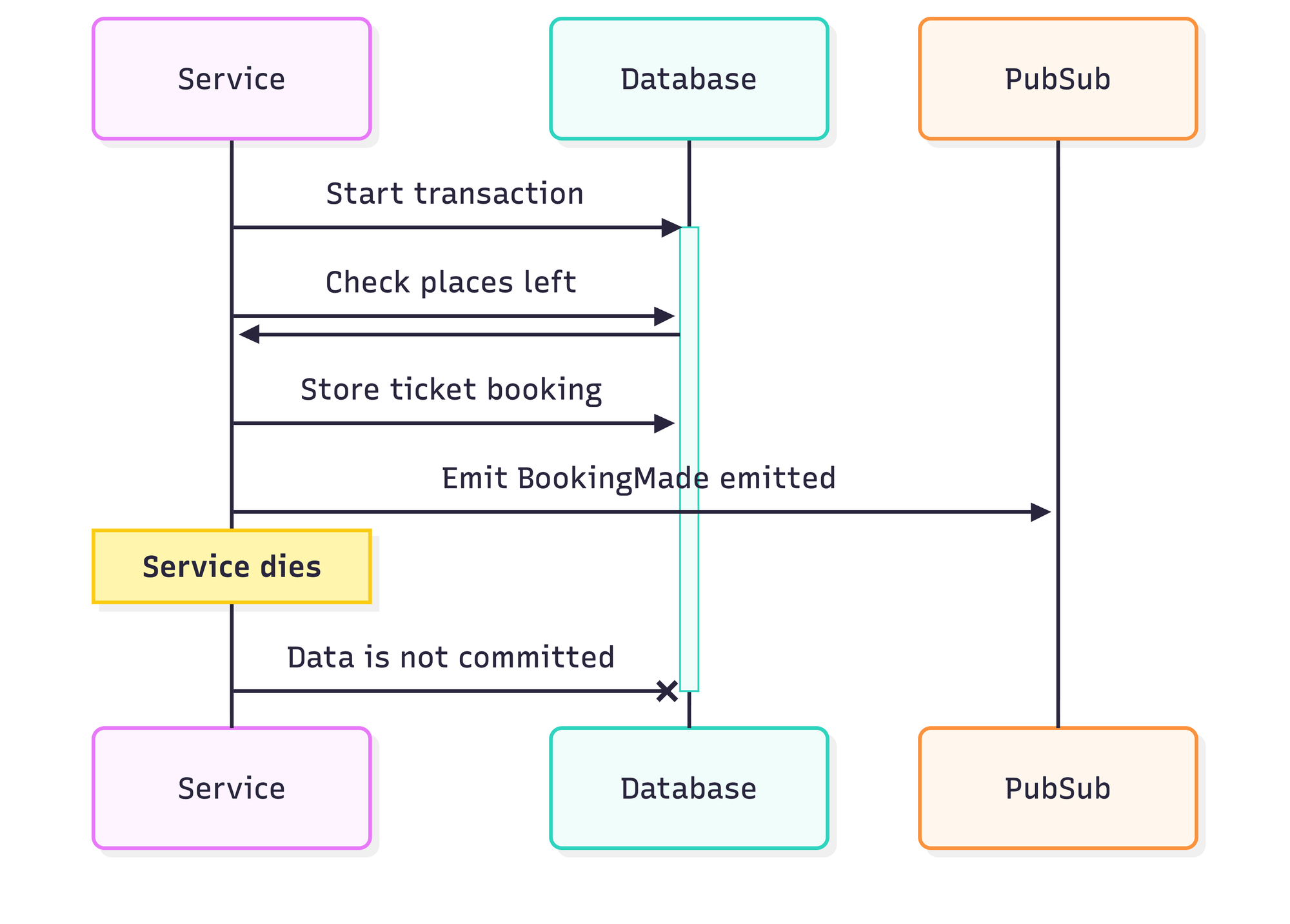

Scenario 2: Publish First, Commit After (The Phantom Event)

Maybe the solution is to reverse the order? Publish the event first, then commit the transaction.

The code would look like this:

func (b BookingsRepository) AddBooking(ctx context.Context, booking models.Booking) error {

tx, err := b.db.BeginTxx(ctx, &sql.TxOptions{Isolation: sql.LevelSerializable})

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer tx.Rollback()

_, err = tx.ExecContext(ctx, `

INSERT INTO bookings (booking_id, show_id, number_of_tickets, customer_email)

VALUES ($1, $2, $3, $4)

`, booking.BookingID, booking.ShowID, booking.NumberOfTickets, booking.CustomerEmail)

if err != nil {

return err

}

var remainingSeats int

err = tx.QueryRowContext(ctx, /* ... */).Scan(&remainingSeats)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if remainingSeats < 0 {

return ErrNoPlacesLeft

}

event := BookingMade{

BookingID: booking.BookingID,

ShowID: booking.ShowID,

NumTickets: booking.NumberOfTickets,

}

if err := b.publisher.Publish(ctx, event); err != nil {

return err

}

// 💥 THE BOOM

return tx.Commit()

}What Goes Wrong

Now the event is published and starts to be processed by subscribers but transaction is not committed yet tx.Commit(), so in case of service crash before it is committed, it will be rolled back and the booking will not be persisted in database.

The outcome:

This is worse than Scenario 1. Here's what happens:

- Third-party service receives the

BookingMadeevent - They generate and email a ticket to the customer

- The customer thinks they have successfully booked a seat

- But the booking doesn't exist in your database

- Your system thinks the seat is still available

- Another customer successfully books the same seat

- Two people, same seat, KISS concert confrontation

This violates your core business constraint: no overbooking.

Why It's Worse

Not only does this cause customer frustration, but it's also harder to detect. The event made it through the system. Tickets were generated. Everyone thinks everything worked. The race condition only becomes apparent when two people show up to the same seat.

Scenario 3: The Network Partition (The Zombie Event)

Let's say you've been careful and avoided the crash scenarios. You commit first, and your service doesn't crash. But distributed systems have another trick up their sleeve: network partitions.

func (b BookingsRepository) AddBooking(ctx context.Context, booking models.Booking) error {

tx, err := b.db.BeginTxx(ctx, &sql.TxOptions{Isolation: sql.LevelSerializable})

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer tx.Rollback()

// Insert booking and check availability

if err := tx.Commit(); err != nil {

return err

}

event := BookingMade{...}

err = b.publisher.Publish(ctx, event)

// 💥 Network timeout! Did it succeed or fail?

if err != nil {

// What do we return here?

return err

}

return nil

}What Goes Wrong

Network issues create insecurity:

- The publish call times out

- Did the event reach the pub/sub? Maybe.

- Should you retry? If you retry and the first attempt succeeded, you'll publish duplicates.

- Should you not retry? Then you're back to Scenario 1 - lost events.

- What do you return to the user? The booking succeeded, but the event status is unknown.

The Dilemma

This case is called a zombie event. The event might be never published or it might be succesfully published with lost response. The biggest twist is that we do not know for certain what happened.

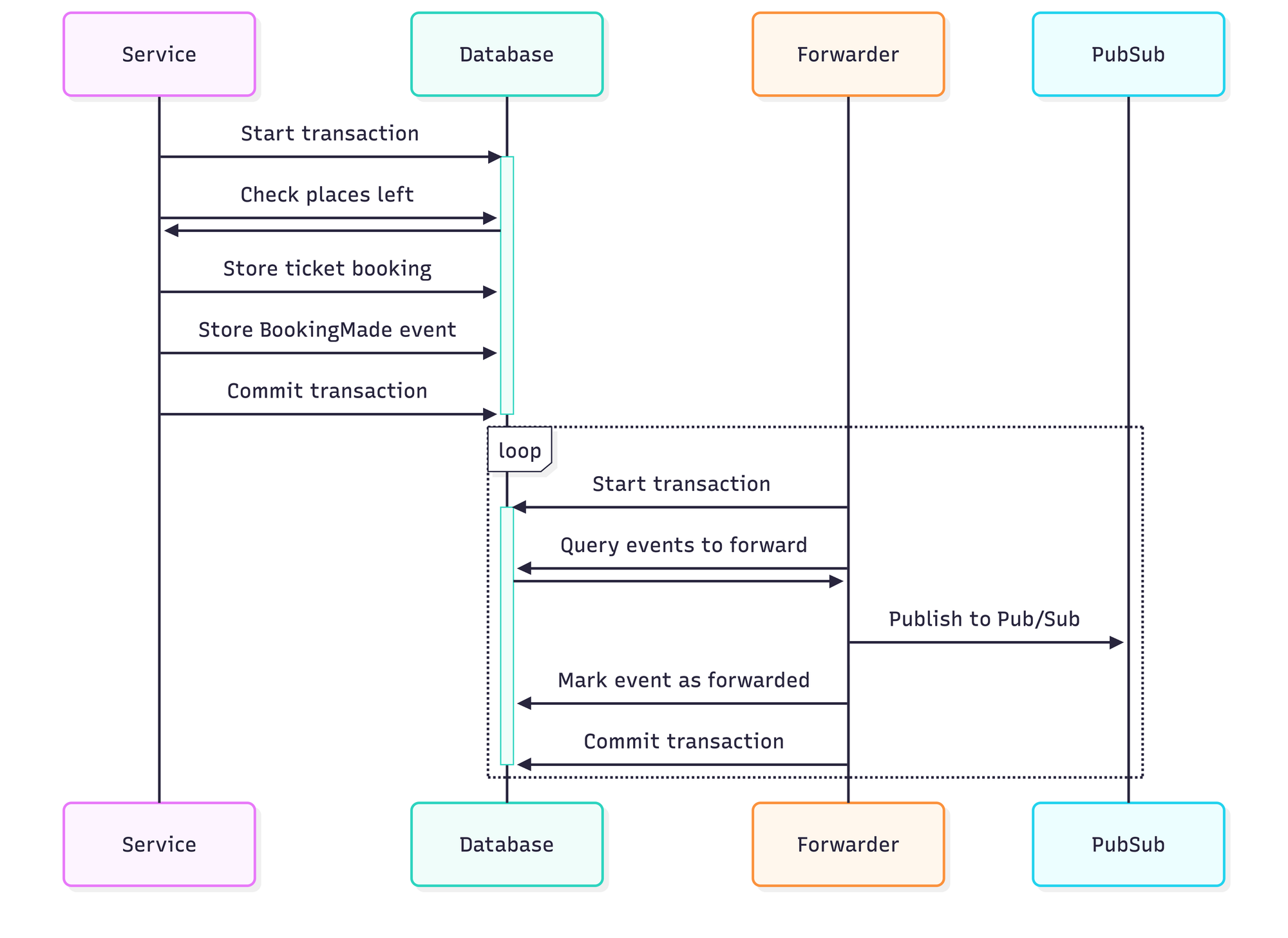

The Outbox Pattern: A Solution to All Three Scenarios

All three scenarios above share a common root cause: you're trying to make two separate systems (your database and your message broker) consistent with each other, but you can't wrap them in a single transaction.

The Outbox Pattern solves this by using a simple but powerful principle:

Store both your business data and your events in the same database, in the same transaction. Then, have a separate process forward the events from the database to your message broker.

Here's how it works:

The two-phase approach:

- Write Phase: The service stores both the booking and the event in PostgreSQL within a single transaction

- Forward Phase: A separate forwarder process reads events from the database and publishes them to the message broker

Now, let's see how this is implemented in the real ticketing system using the Watermill library.

The Real Implementation

1. The Booking Repository

Here's the actual production code that handles booking creation:

func (b BookingsRepository) AddBooking(ctx context.Context, booking models.Booking) error {

return updateInTx(

ctx,

b.db,

sql.LevelSerializable, // Strongest isolation level to prevent race conditions

func(ctx context.Context, tx *sqlx.Tx) error {

_, err := tx.NamedExecContext(ctx, `

INSERT INTO

bookings (booking_id, show_id, number_of_tickets, customer_email)

VALUES (:booking_id, :show_id, :number_of_tickets, :customer_email)

`, booking)

if err != nil {

var pqErr *pq.Error

if errors.As(err, &pqErr) && pqErr.Code == "23505" {

return ErrBookingAlreadyExists

}

return fmt.Errorf("could not add booking: %w", err)

}

// Check available seats

availableSeats := 0

err = tx.GetContext(ctx, &availableSeats, `

SELECT

number_of_tickets AS available_seats

FROM

shows

WHERE

show_id = $1

`, booking.ShowID)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("could not get available seats: %w", err)

}

alreadyBookedSeats := 0

err = tx.GetContext(ctx, &alreadyBookedSeats, `

SELECT

COALESCE(SUM(number_of_tickets), 0) AS already_booked_seats

FROM

bookings

WHERE

show_id = $1

`, booking.ShowID)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("could not get already booked seats: %w", err)

}

// Verify we're not overbooking

remainingSeats := availableSeats - alreadyBookedSeats

if remainingSeats < booking.NumberOfTickets {

return ErrNoPlacesLeft

}

// HERE'S THE KEY: Create an outbox publisher that writes to the database

outboxPublisher, err := NewOutboxPublisher(tx, b.logger)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("could not create outbox publisher: %w", err)

}

eventBus := handler.NewEventBus(outboxPublisher)

bookingMadeEvent := events.NewBookingMade(

booking.BookingID,

booking.CustomerEmail,

booking.ShowID,

booking.NumberOfTickets,

booking.BookingID,

)

err = eventBus.Publish(ctx, bookingMadeEvent)

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("could not publish BookingMade event: %w", err)

}

// If we return nil, the entire transaction commits:

// - The booking is stored

// - The event is stored in the watermill_messages table

// Both atomically!

return nil

},

)

}A couple of things should be pointed out, I use the sql.LevelSerializable, as the strongest isolation level to prevent race conditions. The outbox publisher is created within the transaction, and when the event is published to event bus eventBus.Publish() it is written into database table not message broker. Both booking and event are inserted in one commit together atomically.

2. The Outbox Publisher

Here's how the outbox publisher is set up:

func NewOutboxPublisher(tx *sqlx.Tx, logger watermill.LoggerAdapter) (message.Publisher, error) {

var publisher message.Publisher

sqlPublisher, err := watermillSQL.NewPublisher(

tx,

watermillSQL.PublisherConfig{

SchemaAdapter: watermillSQL.DefaultPostgreSQLSchema{},

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

publisher = log.CorrelationPublisherDecorator{Publisher: sqlPublisher}

publisher = tracing.NewTracePublisher(publisher)

publisher = forwarder.NewPublisher(publisher, forwarder.PublisherConfig{

ForwarderTopic: OutboxTopic,

})

publisher = log.CorrelationPublisherDecorator{Publisher: publisher}

publisher = tracing.NewTracePublisher(publisher)

return publisher, nil

}As shown above, when the sqlPublisher writes messages to table, the decorator pattern is used to add correlation IDs and tracing. At the end forwarder wraps the messages for one special topic "events_to_forward".

This all happens within the same transaction that handles business data.

Behind the scenes, this writes to a table that looks like:

CREATE TABLE watermill_messages (

uuid VARCHAR(36) NOT NULL PRIMARY KEY,

created_at TIMESTAMP NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP,

payload BYTEA,

metadata JSONB,

topic VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL

);3. The Forwarder

A separate process reads from the outbox table and forwards messages to publisher in our case - redis:

const OutboxTopic = "events_to_forward"

func NewForwarder(

db *sqlx.DB,

publisher message.Publisher,

logger watermill.LoggerAdapter,

) (*forwarder.Forwarder, error) {

sqlSubscriber, err := watermillSQL.NewSubscriber(

db,

watermillSQL.SubscriberConfig{

SchemaAdapter: watermillSQL.DefaultPostgreSQLSchema{},

OffsetsAdapter: watermillSQL.DefaultPostgreSQLOffsetsAdapter{},

InitializeSchema: true,

},

logger,

)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

err = sqlSubscriber.SubscribeInitialize(OutboxTopic)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

fwd, err := forwarder.NewForwarder(

sqlSubscriber,

publisher,

logger,

forwarder.Config{

ForwarderTopic: OutboxTopic,

},

)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return fwd, nil

}So look at the factory method, there is passed publisher which publishes this time to redis not database like before. So the sqlSubscriber reads the events from table in database. The forwarder uses as the source database table and as publisher the redis (or any other pub/sub). The forwarder runs independently of the booking request lifecycle. It pulls over and over again the events from database.

How the Outbox Solves Each Scenario

So now when we've explained the implementation details of this pattern let's take a look at the scenarios that we hoped it solves.

Scenario 1 Solved: No More Lost Events

Original Problem: Service commits the transaction, then crashes before publishing the event.

With Outbox:

- The service commits both the booking and the event to PostgreSQL in one transaction

- If the service crashes after the commit, both pieces of data are safely persisted

- The forwarder process (running independently) will pick up the event and publish it

- Even if the forwarder is down temporarily, the event waits in the database

- When the forwarder restarts, it resumes from its last offset and publishes pending events

Result: No lost events. Ever.

Scenario 2 Solved: No More Phantom Events

Original Problem: Service publishes the event, then crashes before committing, causing overbooking.

With Outbox:

- Events are stored in the same PostgreSQL transaction as the booking

- If the transaction rolls back (due to crash, validation failure, or any error), the event is also rolled back

- The event never makes it to the

watermill_messagestable - The forwarder never sees it

- No phantom event reaches third-party services.

Result: No phantom events. No overbooking. Data stays consistent.

Scenario 3 Solved: No More Uncertainty

Original Problem: Network partition during event publishing creates uncertainty - did it succeed or fail?

With Outbox:

- Network issues between your service and the message broker don't matter during the write phase

- The service only writes to PostgreSQL (local, reliable)

- The transaction either commits or it doesn't - there's no ambiguity

- If network issues occur during the forward phase (forwarder → Redis), the forwarder simply retries

- The offset tracker ensures the forwarder knows exactly which messages have been successfully forwarded

Result: No uncertainty. Clear, deterministic behavior.

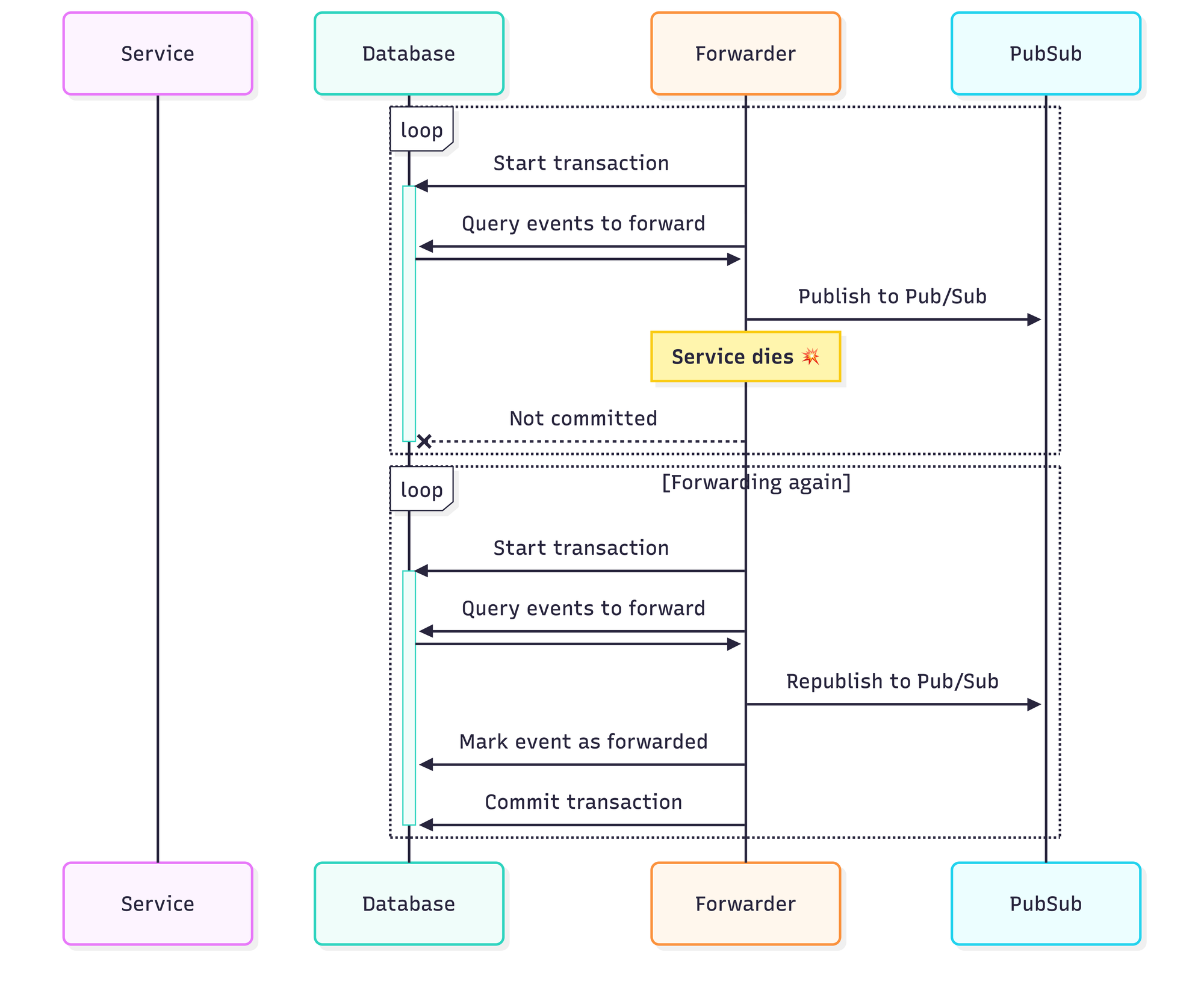

There's One Catch: Idempotency

Notice in the diagram earlier that if the forwarder crashes after publishing to Redis but before marking the message as forwarded, it will republish the message when it restarts:

This means your event handlers must be idempotent - they must handle the same event multiple times without causing incorrect behavior. This is a standard requirement for distributed systems with at-least-once delivery guarantees.

For example:

func (h *BookingHandler) HandleBookingMade(event BookingMade) error {

exists, err := h.repo.BookingProcessed(event.BookingID)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if exists {

// Already processed, safe to skip

return nil

}

err = h.thirdPartyService.NotifyBooking(event)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return h.repo.MarkBookingProcessed(event.BookingID)

}Trade-offs and Considerations

The outbox pattern isn't free. Here's what you gain and what you give up:

Benefits

- Atomic writes: Your data and events are truly consistent. Either both are saved or neither is.

- No lost events: Events are persisted durably before any async processing happens.

- No phantom events: If the transaction fails, the event doesn't exist.

- Built-in crash recovery: The forwarder automatically resumes from where it left off.

- Clear error handling: Errors during the write phase cause transaction rollback. Errors during forwarding are retried.

Trade-offs

- Additional complexity: You need to run and monitor a forwarder process.

- Eventual consistency: There's a delay between committing the transaction and the event reaching subscribers. This is usually milliseconds, but it's not instant.

- Requires idempotent handlers: Your event consumers must handle duplicate events gracefully.

- Database is temporary event store: Your PostgreSQL database now stores events temporarily. You'll need to clean up old messages periodically.

- Transaction isolation matters: The ticketing system uses

sql.LevelSerializableto prevent race conditions during seat checks. This can impact throughput under high concurrency.

Implementation Details Worth Noting

Offset Tracking: The forwarder uses DefaultPostgreSQLOffsetsAdapter to track which messages have been forwarded. This is stored in a separate table:

CREATE TABLE watermill_offsets (

topic VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

consumer_group VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL,

offset_value BIGINT NOT NULL,

PRIMARY KEY (topic, consumer_group)

);Decorators for Observability: The decorator pattern adds correlation IDs and OpenTelemetry traces at both the message level and the envelope level, giving you end-to-end visibility:

- When a booking request comes in, it gets a correlation ID

- This ID is attached to the database transaction

- It's embedded in the event payload

- It's forwarded through the envelope

- You can trace the entire flow from HTTP request → database → outbox → forwarder → Redis → event handler

Schema Auto-initialization: The forwarder is configured with InitializeSchema: true, so it automatically creates the necessary tables on startup. This simplifies deployment but means your application needs DDL permissions.

Conclusion

The Outbox Pattern is a powerful solution for maintaining consistency between database writes and event publishing in distributed systems. By storing both business data and events in the same database transaction, you eliminate the three critical failure modes we explored:

- Lost Events - When services crash after committing but before publishing

- Phantom Events - When events are published but transactions roll back, leading to data inconsistencies

- Zombie Events - When network partitions create uncertainty about whether events were delivered

While the pattern introduces additional complexity through the forwarder process and requires idempotent event handlers, these trade-offs are worthwhile for systems where data consistency is critical. In our ticketing system example, preventing overbooking is non-negotiable, making the Outbox Pattern an essential architectural choice.

The implementation using Watermill demonstrates that this pattern can be applied practically in Go applications with relatively straightforward code. The key insight is simple but powerful: if you can't make two systems transactional together, make one system the source of truth and derive the other from it asynchronously.

Whether you're building a ticketing system, an e-commerce platform, or any distributed system where events must reliably reflect state changes, the Outbox Pattern provides a battle-tested approach to achieving consistency without sacrificing reliability.