Only an idiot has order, a genius controls chaos - why ordering makes sense

Message ordering is one of those problems that seems simple until you actually build a distributed system. I encountered it while working through the go-event-driven training from Three Dots Labs, and it forced me to rethink some fundamental assumptions about event-driven architectures.

The reality check in distributed systems is that messages often arrive out of order. In any distributed system, this must always be considered. A user profile might be updated before it's created. The network doesn't care about your business logic.

What surprised me wasn't that this happens - it's that there are multiple valid ways to handle it, and choosing the wrong approach for your use case can lead to either unnecessary complexity or data corruption. This article explores four different ordering strategies I implemented, focusing on when to use each one and what you're trading off.

The Business Context

Our system processes game events for multiplayer sessions. Players join games, perform actions, and leave. Simple enough, right? But here's what happens in production:

- Player joins Game A

- Network congestion delays the PlayerJoined event

- Player immediately leaves

- PlayerLeft event arrives first

- System tries to remove a player who "never joined"

The same problem appears everywhere in distributed systems:

- Alerts that resolve before they trigger

- Orders that cancel before they're created

- Inventory updates that arrive out of sequence

The core question isn't "how do I prevent out-of-order delivery?", you can't.

The question is:

What ordering guarantees does my business logic actually need?

Let's review together my ideas presented below.

Technique 1: Single Topic Sequential Processing

Let's start with the simplest approach: force everything to be processed sequentially.

How It Works

All events go to one topic. One consumer group processes them in order, one at a time.

eventProcessor, err := cqrs.NewEventGroupProcessorWithConfig(

router,

cqrs.EventGroupProcessorConfig{

GenerateSubscribeTopic: func(params cqrs.EventGroupProcessorGenerateSubscribeTopicParams) (string, error) {

return "events", nil

},

SubscriberConstructor: func(params cqrs.EventGroupProcessorSubscriberConstructorParams) (message.Subscriber, error) {

return kafka.NewSubscriber(kafka.SubscriberConfig{

Brokers: []string{kafkaAddr},

ConsumerGroup: params.EventGroupName + "_group",

Unmarshaler: kafka.DefaultMarshaler{},

OverwriteSaramaConfig: newConfig(),

}, logger)

},

AckOnUnknownEvent: true,

Marshaler: cqrs.JSONMarshaler{},

Logger: logger,

},

)

err = eventProcessor.AddHandlersGroup(

"events",

cqrs.NewGroupEventHandler(func(ctx context.Context, event *PlayerJoined) error {

return gameHandler.HandlePlayerJoined(ctx, event)

}),

cqrs.NewGroupEventHandler(func(ctx context.Context, event *PlayerLeft) error {

return gameHandler.HandlePlayerLeft(ctx, event)

}),

cqrs.NewGroupEventHandler(func(ctx context.Context, event *GameAction) error {

return gameHandler.HandleGameAction(ctx, event)

}),

) What You Gain

- Perfect ordering: Events are processed in exactly the order they arrive at the topic

- Simple mental model: You can reason about your system like it's single-threaded

- No conflicts: Impossible to have race conditions between event handlers

- Easy debugging: Sequential logs make it trivial to understand what happened

What You Trade Off

- Zero parallelism: Processing one event at a time means your throughput is limited

- Head-of-line blocking: One slow event blocks all subsequent events

- Poor resource utilization: Your consumer sits idle while processing one message

- Scales vertically only: Can't add more consumers to increase throughput

When to Use This

This approach is perfect when:

- Your event volume is low (hundreds or low thousands per second)

- Events have cross-entity dependencies (e.g., "process all game events in order")

- Simplicity matters more than throughput

- You're prototyping or in early development

Real-world example: Admin action logs. If you're recording every admin action for audit purposes, you want them processed sequentially. An admin creating a user and then modifying it should appear in that exact order in your audit log.

When to Avoid This

Don't use this when:

- You have high event volume and need horizontal scaling

- Events are independent (e.g., different users, different games)

- You can't afford head-of-line blocking

- 99th percentile latency matters

Anti-pattern: Using this for user events in a multi-tenant system. Why should processing Alice's profile update block Bob's purchase order?

Technique 2: Partition-Per-Entity (Kafka Partitioning)

This is the sweet spot for many systems: ordering guarantees per entity, parallelism across entities.

How It Works

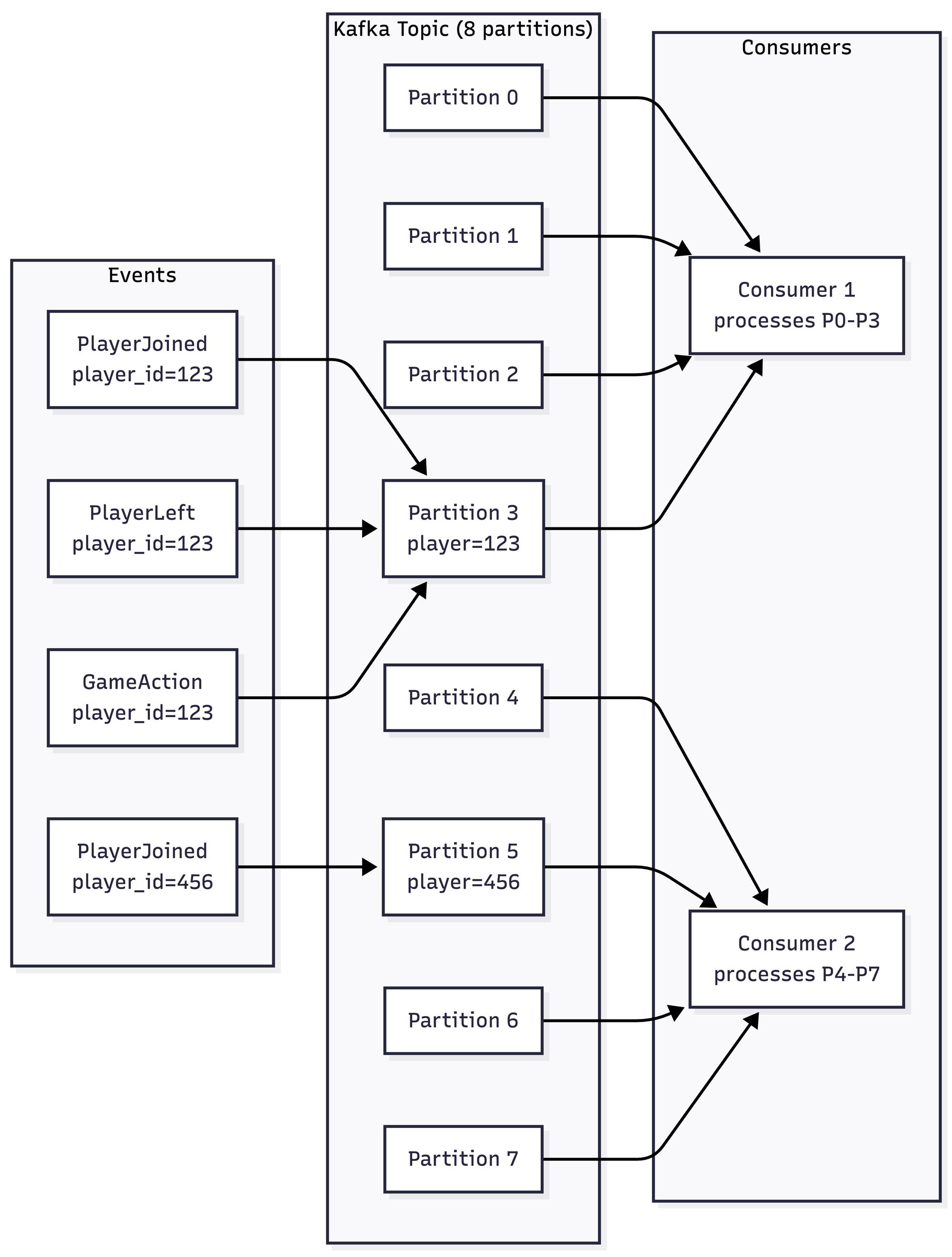

Events for the same entity (player, game, order) go to the same partition. Different entities go to different partitions, allowing parallel processing. In this case we will use metadata which is sent with each message to store the information about which entity should handle this message. Look below:

pub, err := kafka.NewPublisher(kafka.PublisherConfig{

Brokers: []string{kafkaAddr},

Marshaler: kafka.NewWithPartitioningMarshaler(func(topic string, msg *message.Message) (string, error) {

return msg.Metadata.Get("player_id"), nil

}),

}, logger)

msg := message.NewMessage(watermill.NewUUID(), payload)

msg.Metadata.Set("player_id", event.PlayerID)

err = publisher.Publish(ctx, msg)

sub, err := kafka.NewSubscriber(kafka.SubscriberConfig{

Brokers: []string{kafkaAddr},

Unmarshaler: kafka.DefaultMarshaler{},

ConsumerGroup: params.EventGroupName,

InitializeTopicDetails: &sarama.TopicDetail{

NumPartitions: 8,

ReplicationFactor: 3,

},

OverwriteSaramaConfig: newConfig(),

}, logger)Take a closer look at line 8, we are setting up a message metadata player_id base on data from event.

How Kafka Ensures Ordering

Here's what actually happens:

1. Kafka hashes the partition key (player_id)

2. Events with the same key always go to the same partition

3. Each partition is an ordered log

4. Each consumer in a consumer group gets assigned specific partitions

5. Within a partition, events are processed sequentially

All events for player 123 go to partition 3. All events for player 456 go to partition 5. Consumer 1 handles partition 3 sequentially. Consumer 2 handles partition 5 sequentially. Perfect per-entity ordering with cross-entity parallelism.

What You Gain

- Per-entity ordering: All events for the same player/game/order are processed sequentially

- Horizontal scalability: Add more partitions and consumers to increase throughput

- Parallelism: Different entities are processed concurrently

- Good resource utilization: Consumers can be busy processing different partitions

What You Trade Off

- Partition count matters: More partitions = more parallelism, but too many causes overhead

- Rebalancing complexity: Adding/removing consumers triggers partition reassignment

- Limited by entity distribution: If one entity is super hot, its partition becomes a bottleneck

- Ordering only within entity: No global ordering across entities

When to Use This

This is the default choice for most event-driven systems. Use it when:

- Events naturally belong to entities (users, orders, games, devices)

- You need high throughput (thousands to millions of events per second)

- You want horizontal scalability

- Per-entity ordering is sufficient for your business logic

Real-world example: E-commerce order processing. Each order's events (created, paid, shipped, delivered) must be processed in order. But Order 123's events can be processed in parallel with Order 456's events.

Implementation Details Worth Noting

Choosing partition count:

- Too few = limited parallelism, hot partitions

- Too many = coordination overhead, memory waste

- Rule of thumb: Start with 2-3x your expected max consumer count

Hot partition problem:

msg.Metadata.Set("user_id", "power_user_123")

compositeKey := fmt.Sprintf("%s:%s", event.UserID, event.ResourceID)

msg.Metadata.Set("partition_key", compositeKey)Take closer look the compositeKey which is a better choice for high-volume entities.

Partition key choice:

- Use the entity whose ordering matters

- For player events: player_id

- For game events: game_id

- For order events: order_id

- Don't use timestamps or random UUIDs (defeats the purpose)

When to Avoid This

Don't use this when:

- You need global ordering across all events

- Your events don't have a natural entity grouping

- You need to change partition count frequently (causes rebalancing)

- You have one dominant entity (creates a hot partition bottleneck)

Anti-pattern: Using user_id as the partition key when one user (e.g., admin, automated bot) generates 80% of the events. That one partition becomes a bottleneck.

Technique 3: Entity Versioning (Optimistic Concurrency)

Sometimes partitioning isn't enough. What if events are published out of order, not just delivered out of order? Enter version numbers.

How it works

Each event carries a monotonically increasing version number. Handlers reject events with unexpected versions.

type AlertTriggered struct {

AlertID string `json:"alert_id"`

AlertVersion int `json:"alert_version"`

TriggeredAt time.Time `json:"triggered_at"`

}

type AlertResolved struct {

AlertID string `json:"alert_id"`

AlertVersion int `json:"alert_version"`

ResolvedAt time.Time `json:"resolved_at"`

}

type AlertUpdated struct {

AlertID string `json:"alert_id"`

IsTriggered bool `json:"is_triggered"`

LastAlertVersion int `json:"last_alert_version"`

}

var alerts = make(map[string]AlertUpdated)

func OnAlertTriggered(ctx context.Context, event *AlertTriggered) error {

alert, ok := alerts[event.AlertID]

if !ok {

alert = AlertUpdated{

AlertID: event.AlertID,

LastAlertVersion: 0,

}

}

// CRITICAL: Reject out-of-order events

expectedVersion := alert.LastAlertVersion + 1

if event.AlertVersion != expectedVersion {

logger.Warn("out-of-order event",

"alert_id", event.AlertID,

"expected_version", expectedVersion,

"got_version", event.AlertVersion,

)

return nil

}

alert.IsTriggered = true

alert.LastAlertVersion = event.AlertVersion

alerts[event.AlertID] = alert

return eventBus.Publish(ctx, &alert)

}

func OnAlertResolved(ctx context.Context, event *AlertResolved) error {

alert, ok := alerts[event.AlertID]

if !ok {

return nil

}

expectedVersion := alert.LastAlertVersion + 1

if event.AlertVersion != expectedVersion {

logger.Warn("out-of-order event",

"alert_id", event.AlertID,

"expected_version", expectedVersion,

"got_version", event.AlertVersion,

)

return nil

}

alert.IsTriggered = false

alert.LastAlertVersion = event.AlertVersion

alerts[event.AlertID] = alert

return eventBus.Publish(ctx, &alert)

}Take a look on two places, one is checking if events is out of order to avoid processing(acknowledged them without process) those and other in OnalertResolved function, we perform look up of alert, to avoid process alert which do not exists. Detailed timeline and explanation below.

What Actually Happens

Let's trace a scenario where events arrive out of order:

Events published:

1. AlertTriggered (version 1)

2. AlertResolved (version 2)

3. AlertTriggered (version 3)

Events arrive at handler:

1. AlertTriggered v1 → Processed (expected: 1, got: 1) ✓

2. AlertTriggered v3 → Rejected (expected: 2, got: 3) ✗

3. AlertResolved v2 → Processed (expected: 2, got: 2) ✓

What happens to version 3? It's acknowledged (so it doesn't get redelivered infinitely), but it's not processed. This is data loss by design. The assumption is that out-of-order events are rare and can be dropped.

What You Gain

- Strong consistency: Impossible to apply events out of order

- Detects conflicts: Version mismatches indicate a problem

- No phantom state: Can't resolve an alert that was never triggered

- Works with any pub/sub: Doesn't require Kafka partitioning

- Idempotent: Processing the same version twice is a no-op

What You Trade Off

- Lost events: Out-of-order events are dropped forever

- No automatic recovery: If version 2 is lost, version 3+ are all rejected

- Versioning overhead: Every event and entity needs version tracking

- Complex producers: Event publishers must track and increment versions

- State storage required: Handler needs to remember last processed version

When to Use This

Use versioning when:

- Out-of-order delivery is rare but catastrophic

- You can afford to lose occasional events

- Strong consistency matters more than availability

- You have monitoring to detect version gaps

Real-world example: Bank account balances. If you process a withdrawal before a deposit, you might incorrectly overdraw the account. Version numbers ensure transactions apply in order, or not at all.

Another example: Collaborative document editing. If Edit v3 arrives before Edit v2, applying v3 first could corrupt the document. Better to drop v3 and let the client retry.

When to Avoid This

Don't use this when:

- Every event is critical (you can't afford data loss)

- Out-of-order delivery is common

- You don't have a reliable way to generate sequential versions

- Debugging lost events is harder than handling out-of-order events

Anti-pattern: Using versioning for high-volume IoT sensor data where out-of-order delivery is common due to network conditions. You'll drop most of your events.

Critical Implementation Detail: How Do You Generate Versions?

This is the hardest part. Here are three approaches:

Approach 1: Database sequence (strongest guarantee)

func PublishAlertTriggered(ctx context.Context, alertID string) error {

var version int

err := tx.QueryRow("UPDATE alerts SET version = version + 1 WHERE id = $1 RETURNING version",

alertID).Scan(&version)

event := AlertTriggered{AlertID: alertID, AlertVersion: version}

return publisher.Publish(ctx, event)

}Pros: Guaranteed sequential, survives crashes

Cons: Database write per event, doesn't work for event sourcing

Approach 2: Event store append (for event sourcing)

func AppendEvent(ctx context.Context, streamID string, event Event) error {

version, err := eventStore.AppendToStream(streamID, event)

event.Version = version

return publisher.Publish(ctx, event)

}Pros: Natural fit for event sourcing, atomic append + version

Cons: Requires event store, more infrastructure

Approach 3: Timestamp + sequence (weakest, but simple)

type EventPublisher struct {

sequence atomic.Int64

}

func (p *EventPublisher) Publish(ctx context.Context, event Event) error {

event.Version = p.sequence.Add(1)

return p.publisher.Publish(ctx, event)

}Pros: Simple, no database

Cons: Resets on restart, not globally consistent

Technique 4: Independent Updates (Eventual Consistency)

The most sophisticated approach: design your events so ordering doesn't matter.

How It Works

Instead of events overwriting entire state, each event updates independent fields with timestamps. The latest timestamp wins.

type AlertUpdated struct {

AlertID string `json:"alert_id"`

IsTriggered bool `json:"is_triggered"`

LastTriggeredAt time.Time `json:"last_triggered_at"`

LastResolvedAt time.Time `json:"last_resolved_at"`

}

func OnAlertTriggered(ctx context.Context, event *AlertTriggered) error {

alert, ok := alerts[event.AlertID]

if !ok {

alert = AlertUpdated{AlertID: event.AlertID}

}

if event.TriggeredAt.After(alert.LastTriggeredAt) {

alert.IsTriggered = true

alert.LastTriggeredAt = event.TriggeredAt

}

if alert.LastResolvedAt.After(alert.LastTriggeredAt) {

alert.IsTriggered = false

}

alerts[event.AlertID] = alert

return eventBus.Publish(ctx, &alert)

}

func OnAlertResolved(ctx context.Context, event *AlertResolved) error {

alert, ok := alerts[event.AlertID]

if !ok {

alert = AlertUpdated{AlertID: event.AlertID}

}

if event.ResolvedAt.After(alert.LastResolvedAt) {

alert.LastResolvedAt = event.ResolvedAt

}

if alert.LastResolvedAt.After(alert.LastTriggeredAt) {

alert.IsTriggered = false

} else {

alert.IsTriggered = true

}

alerts[event.AlertID] = alert

return eventBus.Publish(ctx, &alert)

} What Actually Happens

Let's trace events arriving completely out of order:

Events published (with timestamps):

1. AlertTriggered at 10:00:00

2. AlertResolved at 10:01:00

3. AlertTriggered at 10:02:00

Events arrive at handler (out of order):

1. AlertTriggered 10:02:00 → Processes first - LastTriggeredAt = 10:02:00 - IsTriggered = true

2. AlertResolved 10:01:00 → Processes second - LastResolvedAt = 10:01:00 - Compares timestamps: 10:01:00 < 10:02:00 - IsTriggered stays true (resolved is older)

3. AlertTriggered 10:00:00 → Processes third - Compares: 10:00:00 < 10:02:00 - Skips update (already have newer triggered time) - IsTriggered stays true

Final state: Alert is triggered (correct!), even though events arrived completely scrambled.

What You Gain

- Order-independent: Events can arrive in any order and produce correct state

- No lost events: Every event contributes, even if delayed

- Natural conflict resolution: Timestamps provide a clear winner

- Highly available: No coordination needed between events

- Idempotent: Processing same event multiple times is safe

What You Trade Off

- Clock skew problems: Requires reliable timestamps across distributed systems

- Complex state logic: Handlers must compare timestamps and merge state

- Limited applicability: Not all business logic can be modeled this way

- Eventual consistency: State converges eventually, not immediately

- Harder to reason about: Mental model is more complex than sequential processing

When to Use This

This is the most advanced technique. Use it when:

- You have truly independent fields (status, metadata, tags)

- Events come from distributed sources with potential clock skew

- High availability matters more than strong consistency

- You can model your domain as "last write wins" per field

Real-world example: IoT device state. A thermostat reports temperature=72°F at 10:00, mode=cooling at 10:01, fan_speed=high at 10:02. These fields are independent. If events arrive out of order, use timestamps to merge them correctly.

Another example: User profile updates. A user changes their email at 10:00 and their avatar at 10:01. If the avatar update arrives first, you should still apply the email update when it arrives. Each field updates independently based on timestamp.

When to Avoid This

Don't use this when:

- Fields are not independent (e.g., status and error_message must match)

- You can't trust timestamps (Byzantine systems, unreliable clocks)

- Business logic requires strict ordering (e.g., "withdraw cannot happen before deposit")

- "Last write wins" doesn't match your domain (e.g., financial transactions)

Anti-pattern: Using timestamps for inventory management. If you have 10 items and two concurrent orders for 5 items each, "last write wins" could leave you with -5 inventory. You need transactions, not timestamps.

Decision Tree

Start here and follow the questions:

1. Do you need global ordering across all events? - Yes → Single Topic(accept low throughput) - No → Continue

2. Do your events naturally belong to entities? - No → Independent Updates (if fields are independent) or Single Topic(if not) - Yes → Continue

3. Can you afford to lose occasional out-of-order events? - No → Continue - Yes and versioning is easy → Versioning

4. Can you trust timestamps across your system? - Yes and fields are independent → Independent Updates - No or fields are dependent → Partitioning

Most common choice: Partitioning. It's the sweet spot for 80% of use cases.

Real-World Hybrid Approaches

In production, you often combine techniques:

Example 1: E-commerce Order System

msg.Metadata.Set("partition_key", order.OrderID)

type OrderStatusChanged struct {

OrderID string

Status string

Version int

}

type OrderMetadataUpdated struct {

OrderID string

LastTaggedAt time.Time

LastCommentAt time.Time

LastViewedAt time.Time

}As you can see it's a combination of partitioning, versioning and indepedent update for metadata.

Example 2: Monitoring System

type AlertEvent struct {

AlertID string

LastTriggeredAt time.Time

LastResolvedAt time.Time

LastAckedAt time.Time

}

type AlertConfigChanged struct {

AlertID string

Config AlertConfig

Version int // Config must apply in order

}

type SystemEvent struct {

Type string // "startup", "shutdown", "failover"

}Well, above it's similar versioning for configuration changes, single topic for critical system events and dedicated system-events for processing sequentially.

Conclusion

Message ordering in distributed systems isn't a single problem with a single solution - it's a spectrum of trade-offs. The four techniques I've explored each occupy a different point on that spectrum:

1. Single Topic Sequential Processing: Simplicity and perfect ordering, but no scalability

2. Partition-Per-Entity: The pragmatic default for entity-based systems

3. Entity Versioning: Strong consistency when you can afford to lose out-of-order events

4. Independent Updates: Maximum availability when your domain model supports it

The key insight is that you don't need to solve ordering if you can design around it. Before reaching for complex versioning schemes or strict sequential processing, ask: does my business logic really require this ordering constraint, or can I model my events to be order-independent?

In the ticketing system I worked on, we used partitioning for most events (bookings, refunds, tickets), versioning for critical financial state transitions, and independent updates for user preferences. This hybrid approach gave us the ordering guarantees we needed without over-constraining the system.

The most common mistake I see is using Single Topic Sequential Processing by default because it's the easiest to understand. That works fine until your event volume grows, and then you're stuck. Start with Partitioning as your default, and only move to stricter or looser techniques when you have a specific reason.

Whatever you choose, make it explicit. Document which technique you're using for each event type and why. Future you (and your team) will thank you.

Sources

- Three Dots Labs - go-event-driven Training: Message Ordering Module

- Kafka Documentation - Partitioning

- Martin Kleppmann - Designing Data-Intensive Applications, Chapter 11: Stream Processing

- Watermill - Event Streaming Library for Go